“Everything is poison, everything is medicine. Both are determined by the dose.” These words are attributed to the famous Swiss physician, alchemist and forerunner of modern pharmacology, Paracelsus. When people talk about the “most dangerous substance”, in most cases they think of the poisons cyanide, arsenic or tetrodotoxin. Although these are quite strong poisons, they are not the most dangerous.

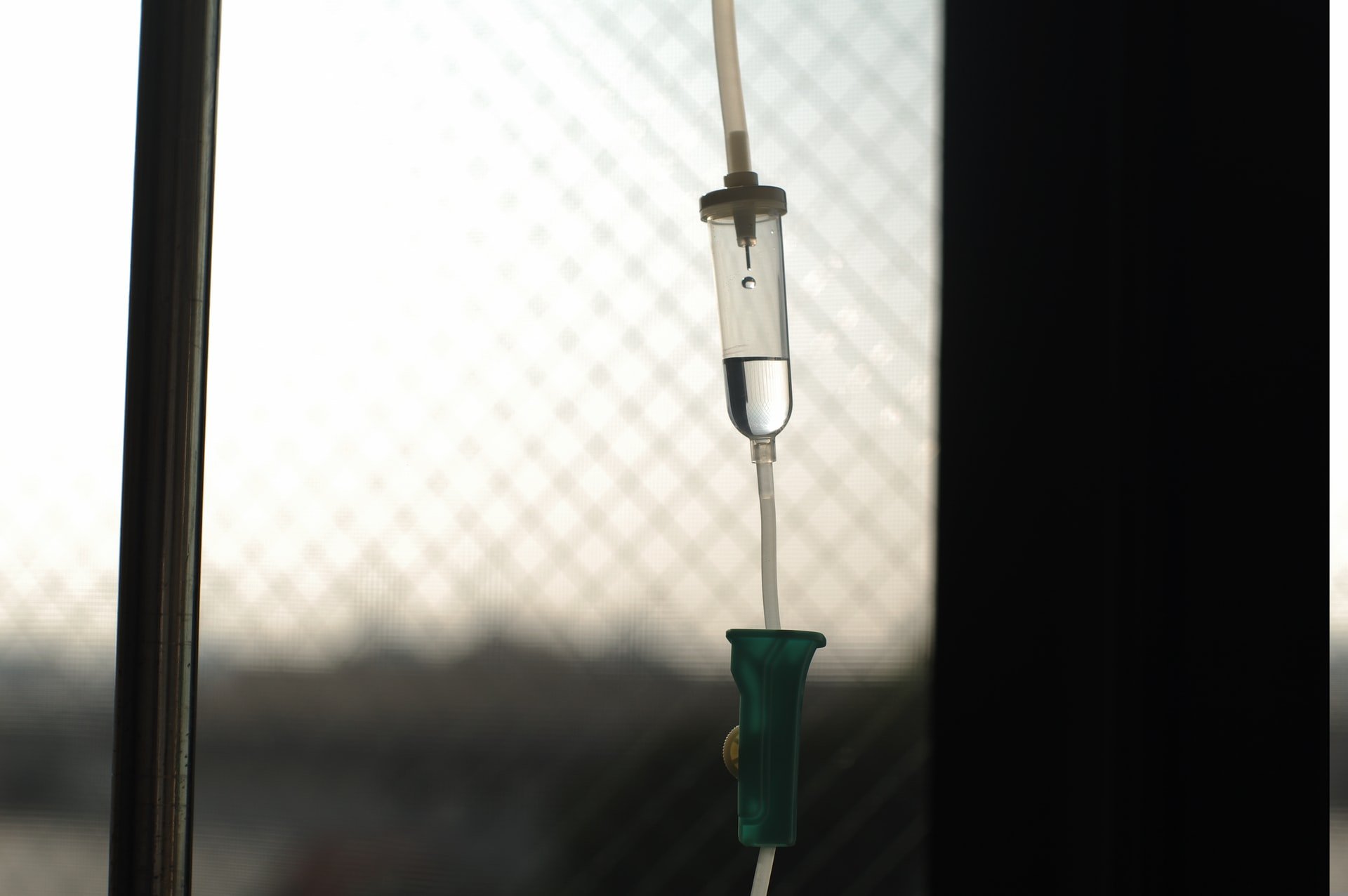

The most lethal substance is botulinum toxin. It is the strongest organic poison known to science. It takes 1 nanogram per kilogram of mass, or one billionth of a gram per kilogram of mass, to produce a lethal dose. Although botulinum toxin is lethal to humans, it is used medically to treat neurological disorders. Also, this substance is widely used in cosmetology to fight wrinkles. Of course, in these cases a purified and weakened toxin is used, which is administered to a person in microdoses.

How the most dangerous poison became the elixir of youth

In December 2021, one of the creators of Botox – the ophthalmologist Alan Scott – died. He was looking for a cure for squint, but the world fell in love with his medicine not because of that. How was the deadly botulinum toxin tamed, and why is it not just to fight wrinkles? The word “Botox” has long since become a household word. And only 30 years ago, people thought the very idea of injecting a bit of poison straight into their face was crazy. After all, Botox is actually made up of the same toxin that accumulates in puffy jars and other spoiled products.

The Sausage Plague

In the 18th century, a wave of outbreaks of a mysterious disease engulfed Germany. Patients’ vision deteriorates, their eyelids droop, it becomes difficult for them to speak and swallow. Many suffer from great weakness. In particularly severe cases, paralysis of the respiratory muscles leads to death. At first, out of habit, the residents blame the witches. But there are those who do not accept this explanation. Germany at that time was conquered by the ideas of the Enlightenment. Universities train doctors who seek to rationally explain observed phenomena. One of them is Justinus Kerner. After graduating from university, he worked as a doctor in a small town and, as befits an enlightened person, wrote poetry and played music. But he goes down in history thanks to botulism research. Kerner became interested in the mysterious poisonings and began collecting information about them. Justinus works like a true modern scientist: after describing dozens of cases, he suggests that the fault lies in a toxic substance in unfresh sausage. Then he conducted experiments on animals, isolated and described the “sausage toxin” (the name of the disease – botulism – comes from the Latin word botulus, “sausage”). Kerner found that the toxin did not affect the cognitive abilities and sensory systems of the patients, but weakened their muscles, which was the cause of the paralysis. Through painstaking experiments, he concluded that the poison blocked signals in the nervous system, thereby disrupting what he called the chemical process of life. “This poison disrupts the conduction of nerves in the same way that rust destroys the properties of an electrical conductor,” he wrote. But Kerner doesn’t stop there. He was the first to propose a medical application of the toxin – for the treatment of diseases associated with involuntary movements. Kerner writes, for example, that in very small doses the toxin can alleviate the symptoms of the so-called dance of Saint Vitus (rheumatic chorea). Kerner’s conjectures were brilliantly confirmed many years later – but were simply ignored in his day.

The failed weapon

In the 20th century, botulinum toxin attracted the attention of the military. Laboratory experiments show that it is the most powerful organic poison known to mankind. According to research by the American Medical Association, just 1 g of the substance in crystalline form is enough to kill a million people. If dispersed from the air in the form of an aerosol, it can neutralize an entire army. In the 1930s, Japan built an extensive research complex to study biological weapons in Manchuria. Director Shiro Ishii admits to exposing Chinese, Korean and American prisoners to botulinum toxin.

Anti-Hitler intelligence had serious (but as it turns out, groundless) suspicions that the Nazis were also studying this poison and planned to use it against infantry. After the end of World War II, it was American military chemists who learned how to synthesize botulinum toxin type A. Ironically, type A was the most lethal, but it would later be used for facial rejuvenation because it worked best on motor neurons. A few decades later, the UN General Assembly banned the development, production and stockpiling of toxic weapons, including botulinum toxin. But the specialists remain. One of these specialists, Ed Shantz, who was involved in the purification of the toxin, got a job at the University of Wisconsin. In the 1970s, ophthalmologist Alan Scott, who was working on a drug for strabismus, wrote to him. At that time, the only effective treatment was eye muscle surgery. Scott was looking for a less invasive method and came across an article about botulinum toxin. In search of the substance itself, he comes across Shantz, who, without much thought, sends him powder with the deadly poison in a metal box by regular mail. Fortunately, no one was injured.

From Oculinum to Botox

Initially, there is no hint of its toxic nature in the name of the drug. Scott registered it in the late 1970s under the brand name Oculinum to treat blepharospasm, a condition in which the eyelids freeze in a half-closed position. Oculinum contains precisely calculated microdoses of botulinum toxin. When injected into a muscle, it disrupts nerve conduction and the spasm disappears. At the same time, patients immediately notice the side effect of the preparation: smoothing of “crow’s feet” around the eyes. But Scott himself does not attach any importance to this – and perhaps misses the chance to become a billionaire. Just two years after registering the drug, he sold it to the Allergan Corporation, which makes contact lenses and other eye care products. But Botox appeared thanks to the persistence of patients. Once an angry patient came to Canadian ophthalmologist Jane Carruthers. “You didn’t fix what I have here,” she says, pointing to the crease between her eyebrows. Carruthers doesn’t immediately understand what’s going on. “When you inject the drug, I get this beautiful, calm look on my face,” the patient explains. Carruthers told her dermatologist husband about the experience and quietly began practicing “beauty injections” on her patients and herself. According to legend, Ronald Reagan himself was among the first connoisseurs of such procedures. But this is unlikely. By 1990, Carruthers had only ten regular patients. At this time it is very difficult to find volunteers even for research. “The typical reaction from people was, ‘What? What do you want to inject into my wrinkles? Isn’t it a deadly poison?” shares Carruthers. The pair presented the first results at a meeting of the American Society for Dermatologic Surgery in 1991, but their colleagues dismissed it as a “crazy idea” that would lead nowhere. But the information about the rejuvenating effect leaked to the press. In 1997, The New York Times published an article with the eloquent headline: “The Drought is Over, Botox Has Arrived.” Botox (as Allergan gives it its name) did not receive official approval for cosmetic use until 2002, when the company managed to convince regulatory authorities that the injections were safe.By this time, Botox had already unofficially treated dozens of conditions, albeit related to muscle spasms: from migraines to bedwetting.

The paradoxes of pharmaceuticals

Today, Botox is primarily known for its application for aesthetic rather than medical purposes. It is often associated with the unnaturally young faces of stars and politicians, specific facial expressions and sometimes with news about victims of unscrupulous cosmetologists, and the procedure itself is offered not only in clinics, but also in spa centers, manicure salons and even in commercial centers. Since the botulinum toxin penetrates all the muscles it can “reach”, the result can be unpredictable if the needle is not inserted correctly or the dosage is not calculated. Side effects occur in one in six customers. Among them – retraction of the eyelids, a feeling of freezing, a “flowing” smile, difficulty swallowing and speech, headache and nausea. In 2003 and 2004, the FDA even sent Allergan a requirement to reduce the risk of side effects. There is also evidence that the risk of side effects increases with frequent use. But the demand is only growing – according to the American Society of Plastic Surgeons, the number of Botox injections has increased by a third since 2010 among young people aged 20 to 29. Meanwhile, new healing properties of botulinum toxin have been discovered in recent years. In 2010, they approved the injection of Botox into the neck and head for the prevention of chronic migraines. And recently, an international group of scientists confirmed its antidepressant effect (this was also suggested earlier). In patients who received Botox injections for various purposes, symptoms of anxiety and depression were reduced by 22-72%. The exact mechanism is not fully understood, but one hypothesis states that when the brain does not receive a signal from “tense muscles”, the processing of negative emotions in the brain is disrupted. Ironically, in the same years that the Carruthers were touting the cosmetic benefits of Botox, scientists discovered an unexpected effect of another already popular drug. In 1992, sildenafil, which was tested as a heart drug, was found to improve blood flow in the pelvic area. This is how our familiar Viagra appears.

“Life is a mystery – says Alan Scott in one of his rare interviews. – Anything can happen and that’s fascinating.”

Photo: Landjäger German sausage by cottonbro / pexels.